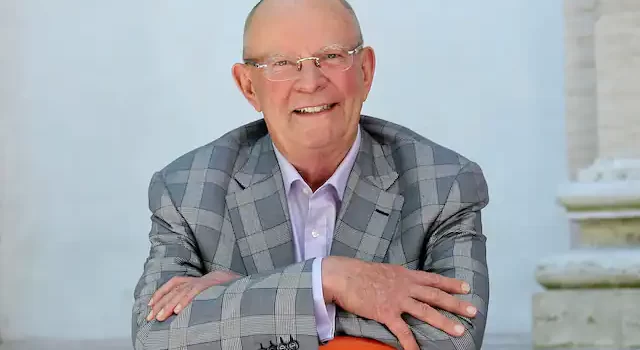

Wilbur Smith, whose swashbuckling adventure novels and historical thrillers examined lust, greed and violence — usually in the hills and savannas of southern Africa — and made him a fixture of bestseller lists around the world, died Nov. 13 at his home in Cape Town, South Africa. He was 88.

Mr. Smith’s novels were filled with bloodshed, bodice ripping and exotic settings, transporting readers to the pyramids of ancient Egypt, a salvage ship in the frigid South Sea and elephant hunts in Zimbabwe. While his books were usually only modestly successful in the United States, they were translated into some 30 languages and found a devoted audience in Britain and Italy, selling more than 140 million copies worldwide.

A former accountant who drafted his first novel on tax forms, Mr. Smith wrote roughly a book a year, drawing inspiration in part from his own life. He survived cerebral malaria as a newborn and polio as a teenager, trekked across the desert on a camel and encountered Somali pirates near a private island he bought in the Seychelles. He said he was charged by elephants and crocodiles, and at age 13, he shot his first lion — or rather three lions, by his telling, after they attacked a herd of cattle on his father’s ranch in Northern Rhodesia.

“Africa is a savage place and always has been,” he told Britain’s Daily Express in 2009, using typically sweeping language to describe the continent where he was raised. “It’s a place of conflict. And my dad looked upon the wilderness as something that should be tamed. He was the one who taught me to hunt. So there’s a lot of blood in my books. There is also a lot of interplay between the sexes. That’s what life is all about.”

To many of his fans, his books were a raucous celebration of bloodstained masculinity and a throwback to the work of English authors like H. Rider Haggard, whose adventure novel “King Solomon’s Mines” helped spur Mr. Smith’s childhood obsession with reading. Detractors accused him of promoting racial stereotypes and noted that he often glorified British imperialism, celebrating White hunters, soldiers and settlers who took up arms against Black Africans and rival Europeans.

On his second try, he dropped politics and focused instead on ranching, gold mining, ivory hunting and the Anglo-Zulu War of 1879. The result, ” When the Lion Feeds” (1964), became a bestseller and introduced readers to the Courtney family, which he followed over multiple generations and more than a dozen novels. He later chronicled the history of another fictional family, the Ballantynes, beginning with ” A Falcon Flies ” (1980); wrote about an archaeological dig inches The Sunbird ” (1972); and created one of his first female protagonists for “The Burning Shore” (1985), about a nurse during World War I.

Several of his novels were adapted into movies, including “Dark of the Sun” (1968), about a band of mercenaries hunting for diamonds during the Congo Crisis; “Gold” (1974), which starred Roger Moore as the general manager of a South African mine; and “Shout at the Devil” (1976), with Moore and Lee Marvin, who became a fishing buddy.

Mr. Smith’s publishing deals were widely publicized in Britain, as was his tumultuous personal life; some of his children and stepchildren said he neglected and abandoned them. “I can be hard. I don’t want to be, but I don’t like being hurt,” he said in a 2015 interview with the Sunday Times of London. “They were important to me at one point, make no mistake — very important — but not now. It’s sadder for them than it is for me, because they’re not getting any more money.”

He had two children from his first marriage, to Anne Rennie — “He definitely, definitely felt he was wasted on one woman,” she later said — and a son from his second marriage, to Jewell Slabbart. In 1971, he married Danielle Thomas, who died of brain cancer in 1999. The next year, he married Mokhiniso “Niso” Rakhimova, who was from Tajikistan and trained as a lawyer. They met at a London bookshop, where he saw her browsing a shelf of John Grisham novels and steered her toward his own work. She was 39 years his junior.

“She was young, in her early 20s,” Mr. Smith told the reporters, “and I was as randy as a stallion in a ranch full of mares.” They later founded the Wilbur and Niso Smith Foundation, which supports young and aspiring writers. Information on survivors was not immediately available.

Late in his career, Mr. Smith began to farm out some of his writing, signing a reported $24 million deal with HarperCollins in 2012 under which he would supervise six novels and work at times with co-authors. Mindful of his mortality, he had insisted on churning out books until his death, telling the reporters, “I know somewhere ahead there is a great brick-red wall, but when I get there I want to be going at full speed with my foot on the accelerator.”

Source: The Washington Post